For my last day in LA, we headed over to LACMA for a walk through the modern art collection, as well as a peek in at the Ed Ruscha retrospective and the Simone Leigh show.

Walks through galleries are often arbitrary—no theme connecting the standings works and the visiting shows—but I had some stuff on my mind: The previous visits to MOCA had me thinking about representation, the Coursera summit about AI and the limits of human consciousness. Maybe some art would dislodge an idea.

In a way, Magritte’s The Treachery of Images sums it all up: Obviously, it’s a painting not a pipe. That’s a pedantic observation. It is indeed a pipe, and a handsome one at that, even as the artist announces his intention to complicate that meaning. Realism, familiarity, deepfakes, apparent sentience, “Death and the Printers”—our perception of the surfaces of language and meaning, of representations and intentions, are all tangled up right now, and it’s difficult to see how they will be untangled in the near future.

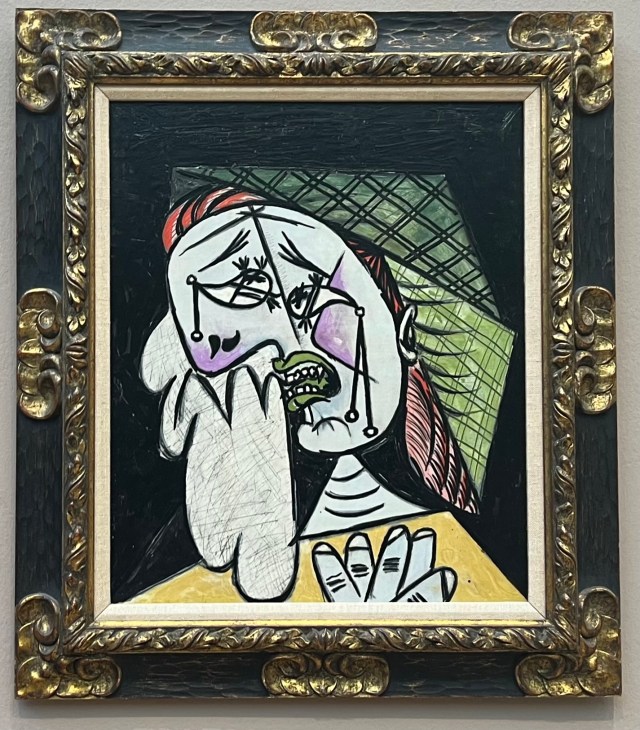

One room of LACMA’s standing exhibit room is entirely given over to Picassos. Sealed away in history and capital these paintings no longer felt scandalously deconstructive.

Pablo Picasso, Weeping Woman with Handkerchief, 1937

Indeed, like Magritte’s comment on the pipe, they seemed a little banal.

Capital had settled on these objects as investment properties. It could have settled on something else. In that settling, it constructed them as value-laden: Great Art. But did they still represent something beyond that capital? Did their explorations of identity and representation stand up as definitive beyond their existence in a financial market? It was hard to discern the answer to that question in the galleries.

By the fourth or fifth room of this stuff I was beginning to wonder if the curators at LACMA knew that women and people of color made art in the twentieth century. There wasn’t much evidence that they did. Certainly capital hadn’t settled on those artists in the same way as Magritte and Picasso. The observation fouled off the story of modernism as a progressively daring encounter with the complexities of representation and suggested a much more crass and self-serving counter narrative of well-policed boundaries for investment that had overwritten whole populations in order to make and protect its case.

It’s pretty tough to walk through the galleries at this point in time and not say “what the hell is going on here?”

If the story of twentieth-century art isn’t about a progressive unpacking of subjectivity in representation, isn’t about plumbing the depths of what it means to be human, what is it about? We wandered downstairs to have a look at the Ed Ruscha show.

While New Yorkers like my mother were slaving away at abstract expressions in the 1950s, Ruscha was out in LA working with typography, photography, and commercial images. “The LA Cool School,” I’ve heard it called in some corners.

Perhaps Ruscha’s most recognizable work is the series Standard Station. I’d seen it but never in person. It’s striking for its flatness, its lack of critique. This is true for all of Ruscha’s work which, aside from a few photographs LA street scenes, features neither people nor politics. There are enormous words—”Annie,” “OOF”— and lots of warehouses, cars, flags and, of course, gas stations but really no people. The verbal statements that emerge within the works are gnomic and elusive. That elusiveness might be the politics, except for the resounding glossy silence to it all. It’s a celebration of color and line, but it also contains within it a dehumanization.

Maybe that’s all there is really. We look at a work, call it a representation, and search for some greater sense subjectivity. “Where are the people in this story?”, we ask. But really it’s neither a pipe nor a gas station nor a perspective. It’s data, and we’re language and image processing machines producing interpretations of what we see.

Or maybe that’s just the outcome of one strand of the story, the strand told by storytellers interested in articulating a canon of artists who are also representations of value on multiple levels, and who circumscribe the boundaries exploration.

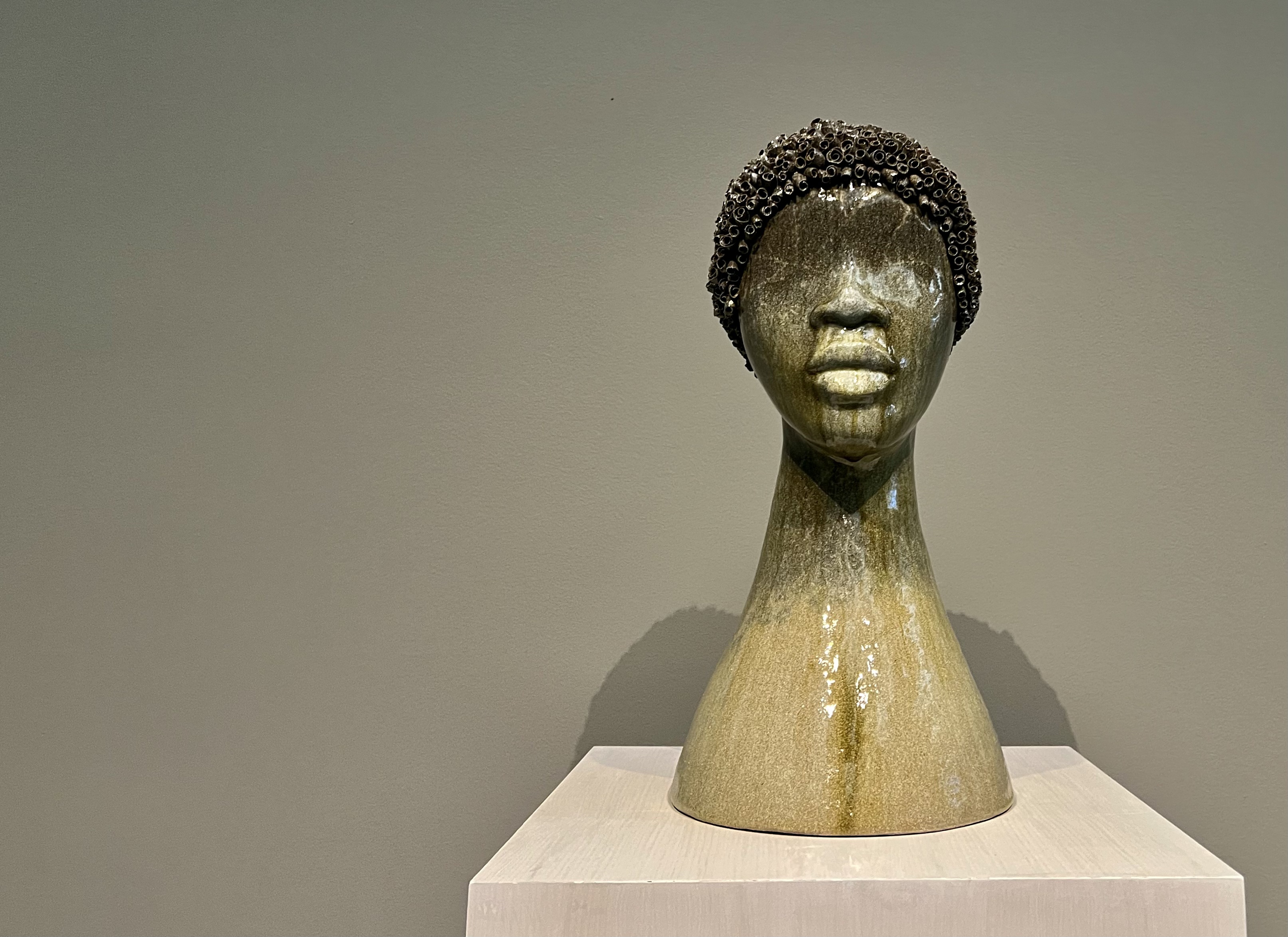

We walked down another set of staircases to the Simone Leigh show. Enormous statues—busts and figures of women beyond human, towers and spirals of shells, a pool with woman fishing in it—stood before us, ancient, otherworldly, and new.

Sculpture by Simone Leigh: Untitled (after June Jordon), 2024; Brooch, 2008; trophallaxis, 2008-2017; Bisi, 2023; untitled, 2021-22.

Hanging from the ceiling over Richelle, its shadows surrounding her, its probes reaching down to perceive her, speak to her, trophallaxis seemed to communicate an intelligence both threatening and fantastic, one that cut across historical narratives—primitive, technological, organic, science fiction, female, alien—aware and powerful.

Once we admit the artificiality of our existing narratives—that the history of modern representation seems threadbare—we are left in a position of instability. What we knew as true now appears untrue. In this position, what emerges outside of that narrative appears as a new form of intelligence.

Call its mode “trophallaxis.”

At the end of the day we went to visit the in-laws, and Floyd was really happy to see me.

To him, I represented “William,” and that was enough.

Sorry, just too good a coincidence to be true: https://youtube.com/shorts/q1xQFi0-M40?si=0mjN5lTtQ_rk_yxQ

LikeLike

This is a wonderful post really!

LikeLike