For the Fourth of July, Helen and I grilled up a rack of ribs, a few ears of corn, some peppers, and a couple of mushrooms. After that we sat down for a double feature: Easy Rider followed by the original Planet of the Apes.

My goal was, of course, to entice Helen into the wonders of motorcycling and, just maybe, prep her to go see the recent Kingdom of the Planet of the Apes, which might seem a tad overly original if one hadn’t seen the 1968 version first.

The two movies shook us both. Maybe it was the pork and the DQ Blizzard. In any case, Helen has gone to lie down, and I’m here at the keyboard, writing it out of my system. We’re not going to see my choice for a triple: Alien

There might be some spoilers up ahead. If somehow you haven’t seen these two movies, stop now.

Ultimately, what these two movies got me thinking about wasn’t the thrill of motorcycling or the challenges of introspection, or what I would do if my spaceship crash landed in place that looked a whole lot like Lake Powell, but where we are this Fourth of July.

Where we are is grim. It’s obvious to say that the country is in a deep struggle over community. Planet of the Apes was written across the sixties and released in 1968. Easy Rider is from 1969. It’s no feat of genius to reflect that the country has faced chaotic times before.

Maybe Jimi Hendrix’s ending to “If 6 was 9,” which rides over a montage of Louisiana in Easy Rider, gives us hope:

I’m the one that’s gonna have to die

When it’s time for me to die

So, let me live my life the way I want to

I’ ‘d like to believe that motorcycling, long hair, and a good bit of rock n’ roll—any commitment to living one’s life the way he, she, or they want to—is a meaningful foundation for happiness. Part of what Easy Rider and Planet of the Apes imply is that such commitments to lifestyle as an ethic is at the core of the problem.

I’m not sure where that leaves us. That bothers me because I like to close the loop in these entries. For now, I find myself standing at an aporia.

Billy: Yeah. Hey we did it, man. We did it. We did it, huh. We’re rich, man. We’re retired in Florida now, mister.

Wyatt: You know, Billy… We blew it.

Recumbent before the last campfire in a movie filled with campfires, Dennis Hopper’s Outlaw Cowboy-Hedonist, Billy, imagines the future for Peter Fonda’s Wyatt, aka Captain America: just across the Gulf Coast Highway lies an ever-golden retirement of wealth and reward. In those lines the American Dream unfurls: the sudden gold strike, the glamorous victory lap of chromed exhaust and candy-yellow-flamed gas tank, years of bloat in Florida.

In this vision, the movie’s resilience. At fifty-five years old, Easy Rider should feel pretty dated. It moves at a slower pace. The heroes aren’t troubled by cell phones or direct messages and they cover the American by-ways at about 40mph, which is good because their motorcycles don’t have functional brakes. Still, the bikes are gorgeous, the soundtrack reverberates, and the landscape is profound. It’s an American road trip.

Timeless.

Of all the iconic power images in Easy Rider—Fonda’s endless legs, the soundtrack, and the two amazing Harleys—Nicholson’s character, Hanson, steals the show.

His death is a particular brutal point in the movie.

In Taos, Nicholson toasts D.H. Lawrence with a first snort of the morning.

At that last campfire, the trip is sinking in for Wyatt. It’s sinking in for us too. Hunkered around the campfire with them, we can’t help but realize the darkening trajectory of communities they’ve visited—the Arizona ranch seemed all right, if you were the patriarch rancher or willing to be ruled over by him. The commune had some charm but also had too many kids and not enough plans or talent—anybody could see that the women were going to get sacked with the little ones when the going got rough and the men decamped for houses with central heating and supermarket-style produce. The diner in Morganza, LA, was a caldron of hate-filled repression that culminated in the brutal murder of George at the parish line. Finally the long-awaited Mardi Gras experience wound out as an extended acid-fueled nightmare in St Louis Cemetery No. 1. The story is a counter Western in which the two antiheroes, versions of the legends Billy the Kid and Wyatt Earp, head back east. Easy Rider is a counter culture film that reverses the Western tropes.

The move’s headliner proclaims Wyatt is searching for America and doesn’t find it. Wyatt doesn’t strike me as that focused. By the end he does realize community is a problem within Easy Rider. It’s a problem outside of it as well. Racial identity is marginalized or rendered invisible throughout, and not in an intentional way. In fact the bikes’ designer, Clifford Vaughs, and builder, Ben Hardy, both Black bikers, received no credit. Easy Rider is of its times and about its times. More surprisingly, it’s about ours as well.

I saw the film back in 1981 in a double bill with The Wild One. I pulled my little Honda CB200 up on the sidewalk in front of a Broadway revival house and swaggered into the darkness as a rite of passage.

The movie shook me then but not so much as now. My high school cohort wore tie-dye t shirts, torn jeans, and M65 field jackets that we curated from Canal Street army surplus stores and basement vintage boutiques. The sixties was our Golden Age of visionary rebellion, distanced not by years but by the vast chasm of decadence represented by all that was Studio 54. We dressed ourselves in its remnants to escape our fallen epoch.

Nicholson’s George articulated what I believed:

George: Oh, they’re not scared of you. They scared of what you represent to ‘em.

Billy: Hey, man, all we represent to them, man, is somebody who needs a haircut.

George: Oh, no. What you represent to them is freedom.

Like George, I saw motorcycles and long hair as representing freedom. More: I saw in them the ability to test my mettle and to stand apart at the same time, heroically and rebelliously. Honestly, I guess I still do.

As Helen and I reflected on the movie, we combed through Billy’s hair. Throughout the movie, Billy’s hair transfixes Cop and Good-Ole Boy alike. They read his wavy locks as gender trouble, a breach of code that admits all manner of fantasy: promiscuity, role reversal, forbidden desire.

Then and now, gender expression represents a basic freedom to control one’s body. It was and is a lightening rod for the fear of such freedom.

That’s what pulls me up short this time through Easy Rider. Forty years after my first screening the country is locked in the same struggle. It still imagines that the dream of an unexamined life in Florida is a great reward, is still unable to contrive a sustainable community that includes race, and is still fighting for individual freedoms for gender and body decisions.

George rhapsodizes over some lost American past. “You know,” he muses by that campfire, “this used to be a hell of a good country. I can’t understand what’s going on with it.” The movie doesn’t show us anything nostalgic worth pining over beyond the physical landscape. His lines sound like memories of a naive childhood. When Wyatt tells Billy “we blew it,” I hear the line both as a condemnation of their personal lack of imagination and as a reflection on the collectivity of America.

Talk about long hair and role reversals.

After Easy Rider we probably should have kicked our jiffy stands down and enjoyed something anodyne (Harleys don’t have “kickstands, they have “jiffy stands”). I never know when to quit. I keyed up Planet of the Apes, and Helen went along for the ride.

Planet of the Apes felt a lot tamer than Easy Rider.

That’s just the 1968 Hollywood sets.

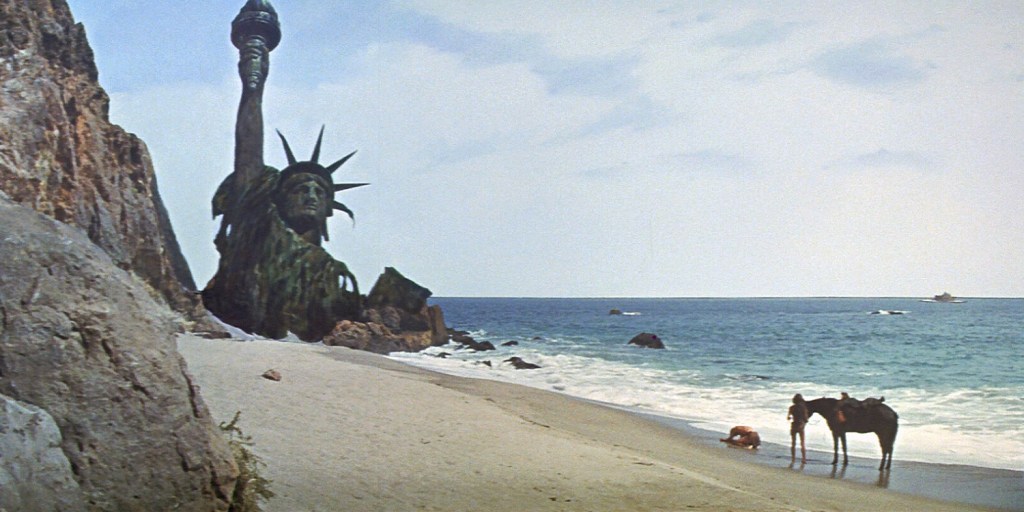

My mother took me to Planet of the Apes back in the early seventies. We got in late, but it didn’t matter. The movie mesmerized me, and the ending blew my mind.

What struck me this time is how tightly the movie weaves its strands of despair. Charlton Heston’s Taylor is an astronaut sick of humanity and dying to get off earth. He’s arrogant and macho and self-involved. He’s a man of action and not much of a communicator. That doesn’t serve him too well on the planet of the apes, but he gets by.

He comes to a world that smacks him in the face with the very codes he’s trying to escape: racial superiority, religious dogma, scientific hypocrisy, barbaric treatment of those it deems animals, and, ultimately, nuclear annihilation.

Taylor is appalled by human and ape alike. Flipping the roles around—putting him in the cage—makes humanity’s collective inhumanity plain. But Taylor is the last twentieth-century man as well. He’s the epitome of the terms he now condemns, and so his condemnation is for himself as well.

“We blew it,” says Wyatt, and by the end of Planet of the Apes, Taylor certainly agrees.

“You finally really did it. You maniacs. You blew it up. Ah, damn you. God damn you all to hell.”

Apologies for any typos. I wish you all the very best.

Thanks to Wikipedia and Movie-Locations website, https://movie-locations.com/movies/e/Easy-Rider.php., as well as npr: https://www.npr.org/2014/10/11/354875096/behind-the-motorcycles-in-easy-rider-a-long-obscured-story