from Le Danse Macabre (Matthias Huss: Lyons, 1499)

The first-ever image of the printing press appears, strangely, as a story of Death.

Printing was developed across the 1450s in a halting progress of experimentation. Johannes Gutenberg had taken a number of loans for various financial schemes. Printing paid off, but not quickly enough: Gutenberg’s creditors foreclosed on him and seized the technology. The rest is history.

Matthias Huss, working in Lyons some fifty years later, included the woodcut, now known as “Death and the Printers,” in a book called the Danse Macabre. The Danse Macabre features Death visiting every station of life—the King, the Priest, the Merchant, and so forth, down to the lowly begger. Huss included the print shop and the bookseller’s stall in his version, and thus turned a generic crowd pleaser into a contemporary commentary on the disruptive force of new communication technology.

The woodcut is done with care. We see the compositor at work picking type from the lower case (capital letters were stored in the upper case, small letters in the lower case) and putting it in his shooting stick, the form resting on his bench. He is annoyed at Death’s interruption. Death grabs the pressman’s hand and points the way for him. The inker—with this huge ink dauber coated in pasty ink—gasps. The press, standing almost as tall as death itself, is represented with some detail. It is nailed to the ceiling with boards so it does not walk across the floor as the pressmen pulls the bar. Even the bookseller in the right-hand panel is created with his books stacked, not stood, as was the medieval practice.

Death obscures. It interrupts. It shows us technology fraught with peril. In the woodcut there are four laborers, and only three corpses. The press itself looms in the room, towering over the workers, as the fourth Death.

The image is a message from the past about disruption. It tells us printing was not simply a change in book production, but also in labor, in reading, and in power. It is estimated that twenty-million books were printed in Europe between Gutenberg and Huss. This introduced the book as an object that could be owned and shared, an object not simply of authority but also of intimacy. Owning a book and having unmediated access to its content changes the owner into a reader—of stories, of law, of history, and of spirituality. The woodcut, in its survival, also reminds us that as much as death and the printers marks the end of a way of life, printing transcends time, a newly accessible form of immortality .

Launched out of Stanford in 2012 as a Massive Open Online Course platform, Coursera has evolved into the major provider of online learning at scale. That is, where some online education companies simply build powerpoint lectures a student can click through and others attempt to recreate a classroom experience over the internet using Zoom, Coursera has built a massive subscriber base and a major portfolio of classes and degrees uniquely suited to the internet’s scale. Their courses are largely open access, purchasable separately from university enrollment, complete with readings and assessments, and run at any time.

I got on board with Coursera in 2013 and didn’t look back until just this year, when I returned to the Department of English.

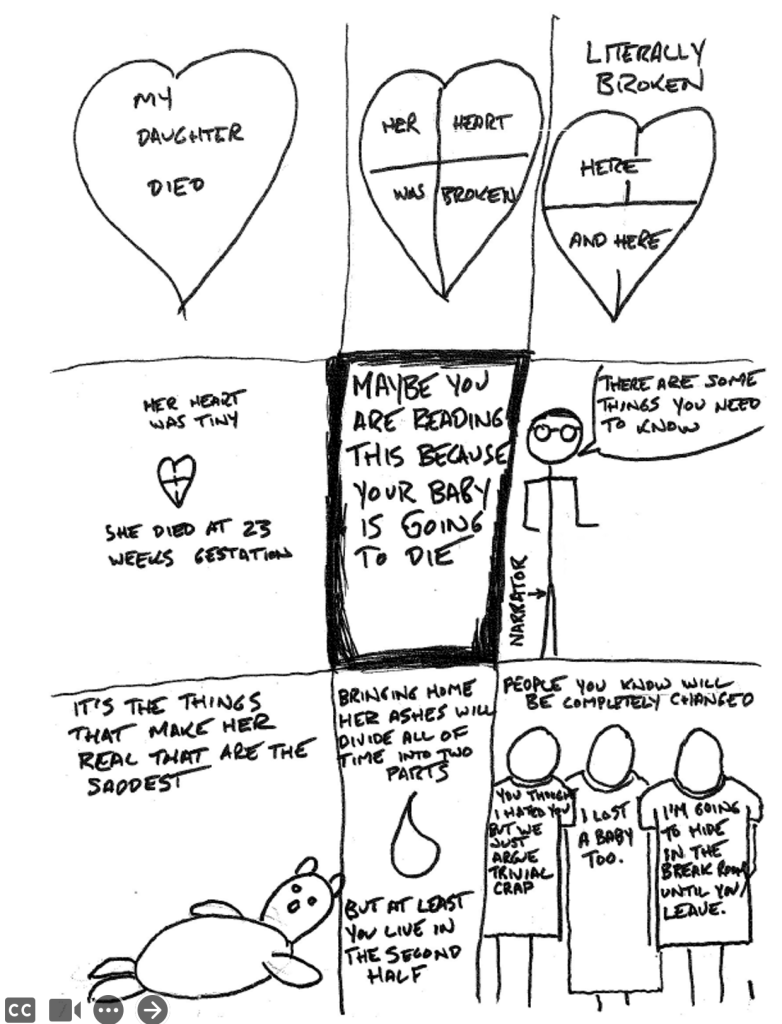

My presentation at Coursera’s Future of Higher Education Conference focused on technology disruption by looking at the beginning of printing and at my experience in 2013 teaching an early massive online course of 38k students on comics and graphic novels. I argued that in both cases technology reshapes human relations with communication technology so as to create a newfound sense of intimacy.

Indeed, one of the comics my students made in the course, a powerful autobiographical story of miscarriage, ends “Your grief is intensely personal, but you don’t have to be alone”—a reminder that even an online course of thousands need not be anonymous.

AI is a major presence in Higher Education already, already, in a way, a death of past practices. In another way, however, it marks a new emergence in access to knowledge that will produce new intimacies and new modes of learning.

Like Huss, we know change is upon us but cannot imagine the final result.

One unexpected joy was running into an old colleague from The University of Southern Mississippi, Hattiesburg. Russ was the HR director when I was there and is now a Provost.

The two of us navigated Katrina together. I remember, chair of English for only a few months when the storm hit, sitting in his office trying to figure out how new faculty would be paid. The experience of making a real-time difference sealed my career in academic administration.

Capital destruction (money death) drives technology’s advance. The dot-com bust destroyed trillions of dollars of investment, but the bankruptcy of Global Crossing et al left the world with vast amounts of fiber making broadband more affordable; and stranded investments in chips, hardware, and software fueled the subsequent internet boom.

We’re probably going to see the same with AI. Sequoia argues that capex is vastly outrunning revenue. NVIDIA is making money, but service providers are losing it. That’s going to help end users but not necessarily investors.

LikeLiked by 1 person