Last weekend my wonderful spouse and I went to two movies, probably more than we’ve seen in the past six months. This sudden burst of cinematic appreciation was inspired by my colleague Bob’s mention that the American Shelby Collection was just up the road, tucked away in Gunbarrel, CO, so off we went to see Christian Bale and Matt Damon in Ford v. Ferrari as prelude to my trip up to see the cars. The next day we followed up with a matinee viewing of Sam Mendes’s film, 1917.

We were happy to have seen both. Ford v. Ferrari, out at the very moment of Ford’s release of the new Shelby GT500, smacks of a bit of marketing. Still, it’s a good show. 1917 was better by a fair bit. Both movies generate intensity—the GT-40’s tachometer needle diving and diving again into the red zone is truly thrilling—but 1917 unfolds through what appears to be three long takes, and so it feels almost a theatrical performance. One watches with baited breath, amazed the actors—let alone the characters—make it through the scene!

Both movies intersected with some of my thinking about motorcycling, too, telling the glory of internal combustion at the beginning and the beginning of end of it all.

Ford v. Ferrari is about the 1966 Le Mans endurance race in which Ford’s GT-40 race car, fettled by Carrol Shelby and particularly by his English driver Ken Miles, swept first, second, and third places, besting Ferrari.

And there it was, sitting up in Gunbarrel with its big grin—that third hero of the movie—the very GT-40 that Ken Miles drove in 1966. The museum is great, packed with cars and memorabilia, but small enough to be comprehendible. A solid runner up to Miles’s GT-40, for my attention at least, was the Shelby GT350-S, in a beautiful Ivy Green, a 1965 Mustang developed as a prototype supercharged Mustang.

The gentleman behind the counter gave Ford v. Ferrari “A+ for entertainment value and C+ for history.” I asked him what was wrong with it, but his answer was drowned out by the sudden starting up of the GT-40 Mario Andretti ran at Le Mans in 1967. I did make out his objection that Shelby had been involved in tuning Mustangs well before the movie makes out. And that Mathew McConaughey would have been a better choice for Carroll Shelby. I couldn’t argue with that. Two Texans. Shelby was tall, weathered, and wiry, cynical looking by the way of Steve McQueen. Matt Damon gave an earnest performance, but he has a perpetual school-boy look that doesn’t fit.

Christian Bale, however, was perfect.

The truth of the movie, as well as of the museum, is about heroism. The Mustang, the Cobra, Shelby & Ford’s trifecta at Le Mans, like the Apollo mission, all embody a spirit that Americans hold close. Don’t look too carefully at the fact that Ford was by then a multinational conglomerate, and Ferrari still essentially a cottage shop, producing in 1965 just over six hundred cars. The cars and Shelby, too, are in some deep way tied to individuality, to heroic measures, to mastery, risk, adventure, and success against odds.

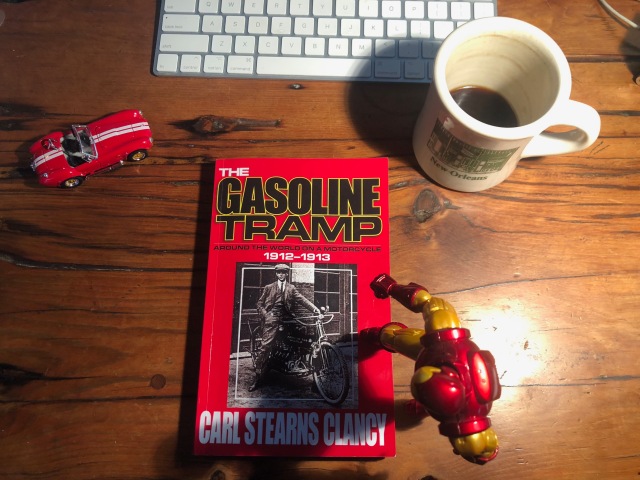

I just finished reading Carl Stearns Clancy’s The Gasoline Tramp, a narrative of his 1912 trip around the world at 21 years of age. For me, the book connected to 1917 as a glimpse into a world thrown into sudden change—from Clancy’s trip in 1912 to the middle of World War I in a few years.

Clancy is the first man to go around the world on a motorcycle—18,000 miles in ten months. Starting out in Philadelphia with his photographer friend, Walter, who in a strange connection to ol’ Ewen McGregor’s camera man, also had no motorcycling experience, they sail to Dublin, then on to Glasgow and London, next to Belgium and then Paris. After Paris, Walter heads home, and Clancy goes on alone, through Spain to Morocco and Algiers, then to Italy. In Naples he is convinced that India is unpassable by bike, so he takes a boat to Ceylon (Sri Lanka), and then on to Singapore, Hong Kong, Shanghai, and Japan, disembarking to explore at each port. In Japan he learns that his mother is ill, and he quickly sails back to San Francisco. He is the first rider from San Francisco to Portland. It seems the hardest riding of the entire trip is from Spokane across the west to North Dakota, at which point things apparently lighten up.

He has guts, this Clancy kid. He begins as if on a lark and never looses his cool. “Have you ever eaten too many peanuts and become so fed up with them that you felt you never wanted to look a peanut in the face again?,” he starts off, “Well, that’s just the way I felt about work in August 1912.”

How many of us have eaten those peanuts and known that feeling, but kept eating all the same?

Clancy rides a Henderson, a motorcycle brand begun by William and Tom Henderson in 1911. In 1912 Henderson came out with a 934cc four-cylinder bike, a giant of the day, making a whopping seven horsepower. Clancy seems to have gotten an early one, with a contract to promote the company on his round-the-world tour. As it turns out, he signs on a Parisian dealer for 100 bikes, financing his entire trip, and at the very end he reports that he set out with $270 dollars and has $200 dollars still in his pocket.

Throughout, Clancy’s American pluck and resourcefulness is delightful. He’s mercantile—ever with an eye to selling those Hendersons—but not exploitive, lamenting his every encounter with commercialism:

We passed through Londonderry the next noon, and by four o’clock reached the Giant’s Causeway. Leaving our machines at the hotel, for, unlike Donegal, the Causeway is sadly commercialized, we descended a winding path along the face of the magnificent cliffs for over a mile, when we were anything but pleased to find ourselves confronted by an iron fence, and charged sixpence admission to his remarkable freak of nature.

He’s resourceful. He apparently uses only one pair of Goodyear tires most of the way, regretfully but dutifully replacing them in Colombo, Sir Lanka, with a pair he had sent ahead. He tells us gas is about 90¢ a gallon the world over, but 20¢ in Los Angeles . The Henderson turns 60mpg on average (better than any of my bikes). He’s proud to tell us that he gets by in Paris on $1.00 day. He’ll fight all day long, and into the next day, for what he sees as a fair price, but he’s also anti-colonialist:

In all Ceylon, I came across but one school, and I found it hard to suppress entirely a feeling of disgust at the manner in which the “planter-aristocracy” conducted themselves—ordering around (as if they were dirt under their feet) the descendants of a race who had ruled royally before England was discovered.

The Gasoline Tramp is also naïve about what is in store. Looking at some medieval instruments of torture, Clancy thinks “thank God for the humane spirit of our time, which makes such fiendish cruelty impossible!”

It was a chilly twenty minutes from my house up to the Shelby American Collection—just enough time for the bike to get warm and for me to get cold. Even that ride, though, felt evocative of much more, as my picture below testifies. Ford v. Ferrari, the Shelby American Collection, The Gasoline Tramp, are all about this evocation, about the provocation of internal combustion, about the American myth as it charges down the road, as it belts out ever more horsepower, as it bests Italian design, indeed makes its way all the way across the globe.

1917 forms the dark shadow of this heroic venture, telling the horror of mechanized destruction wrought across the face of the earth, its humans, its wilderness, and its animals. The image that stays with me from 1917 is a piece of the background, a face embedded in a trench’s mudded wall, frozen in a terrible silent scream.

“Thank God for the humane spirit of our time.” Clancy had no idea what was merely a few years away. One can’t help wonder what lies ahead of us now.